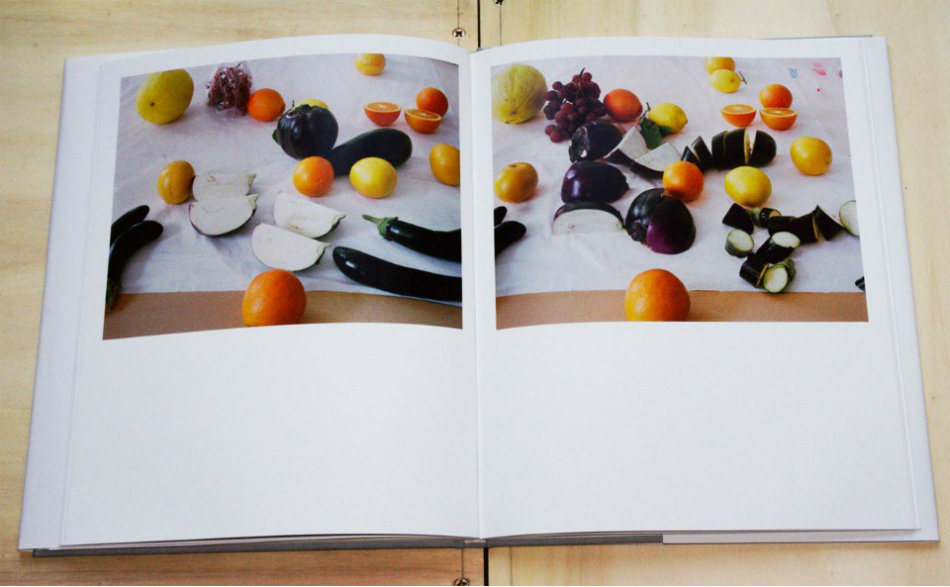

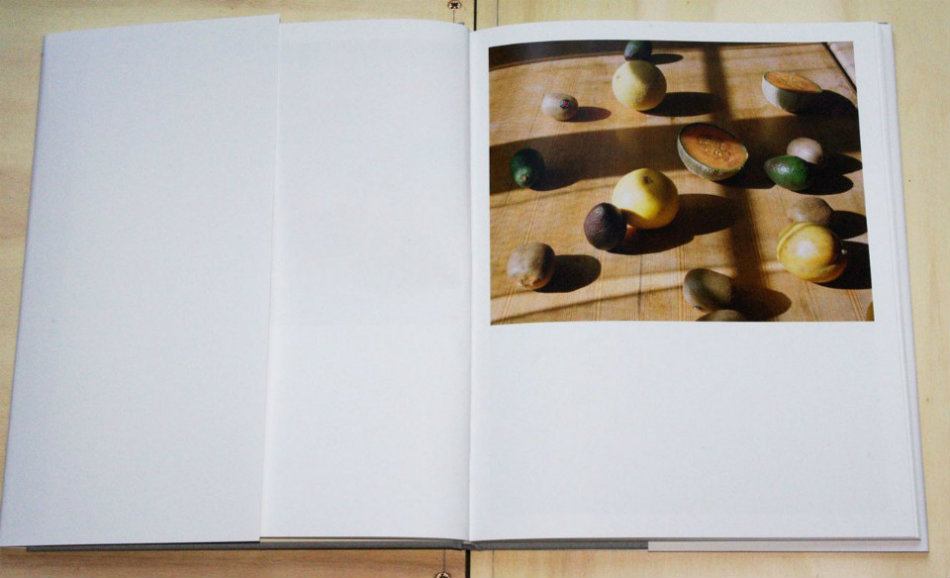

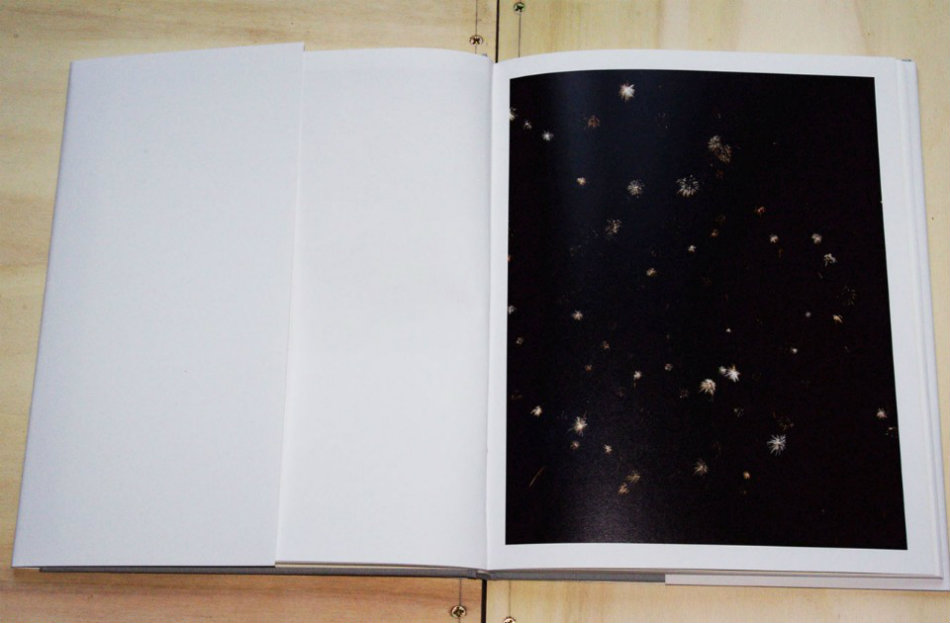

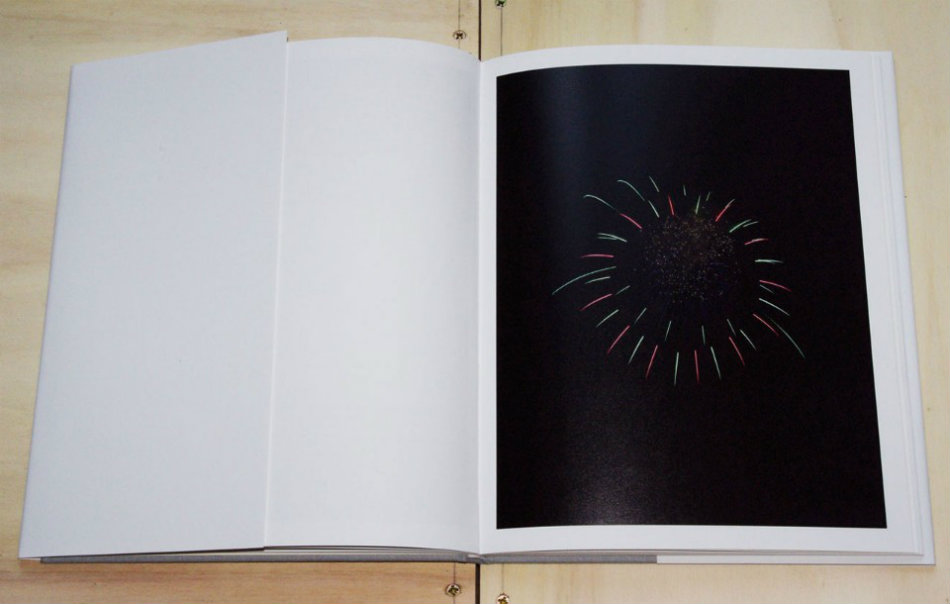

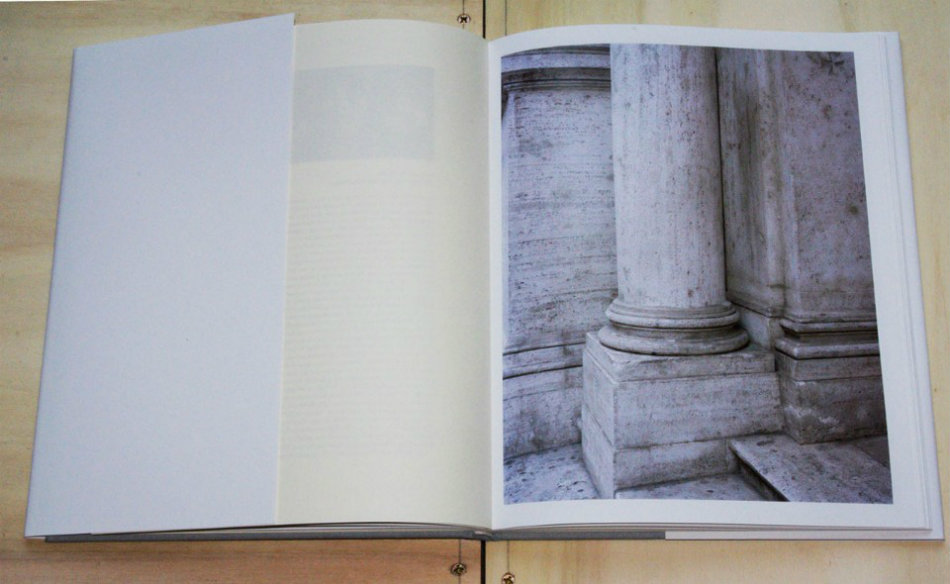

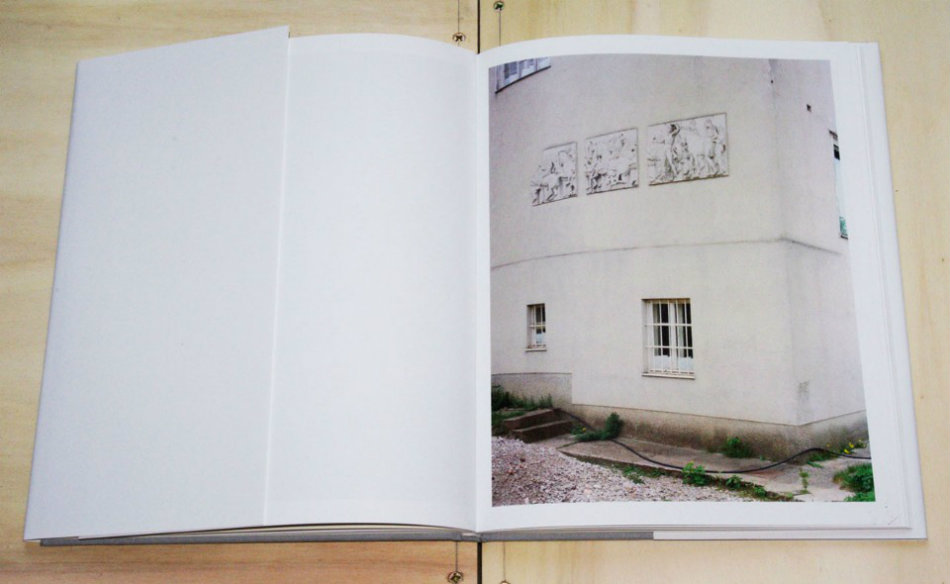

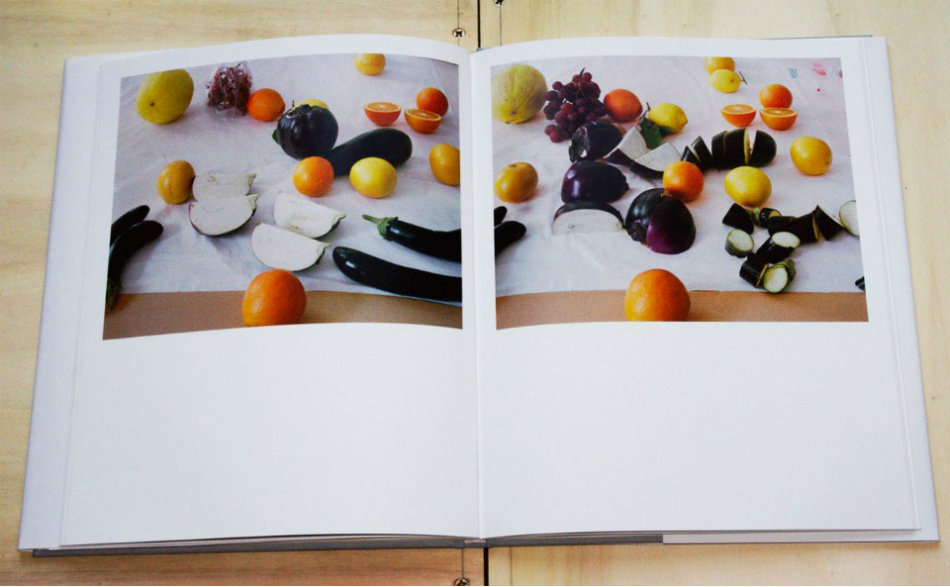

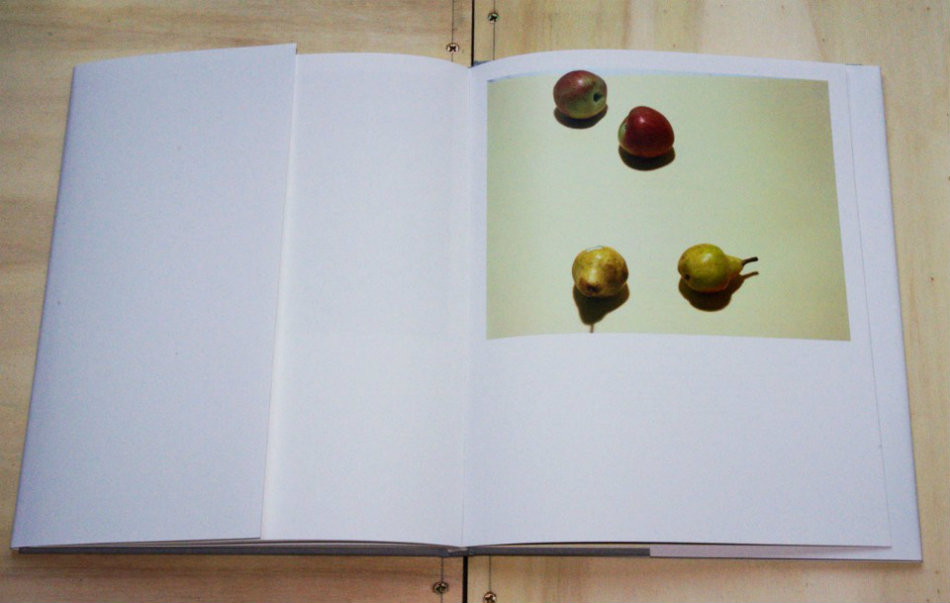

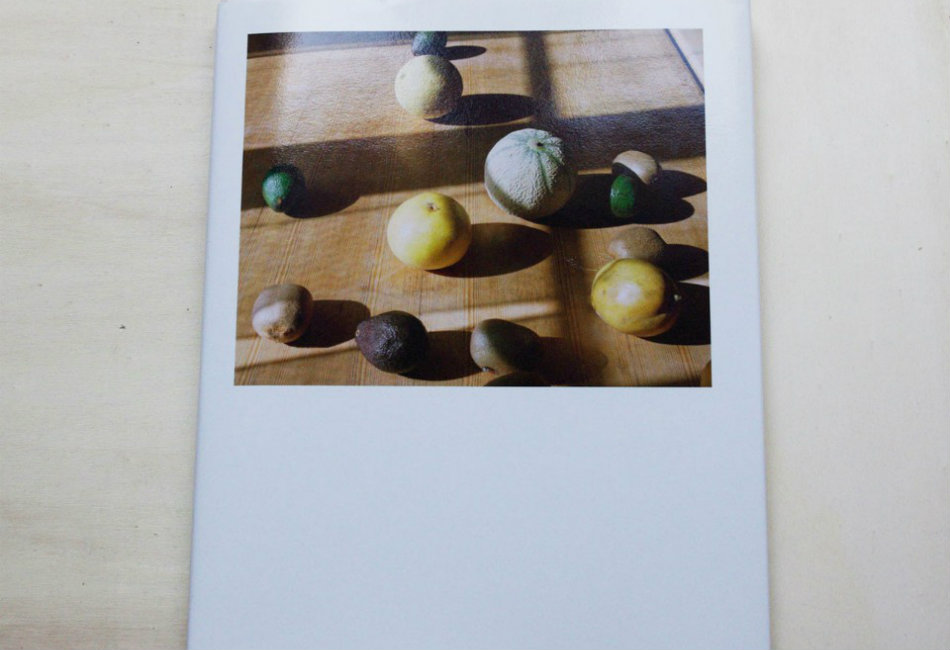

Stefano Graziani’s latest book, Nature morte (words by Nanni Cagnone and Pier Paolo Tamburelli, Galleria Mazzoli Editore, Modena 2016), is eclectic and his fourth published with Modena gallery owner Emilio Mazzoli, accompanying an exhibition of the same title, on until 8 October. The book contains photographs from several lines of the Trieste photographer’s research; some are older (architecture) and others more recent (fireworks) but all are presented as part of the same genre – still life. The subjects of Graziani’s latest pictures have no allegorical or metaphorical meaning, they are “things for their own sake” and have also been exhibited this year at Fotografia Europea in Reggio Emilia and published in another recently printed book, Fruits and Fireworks (A&Mbookstore, Milan 2016).

Nature morte features the striking presences of a minor Roman baroque church, Santa Maria in Portico in Campitelli by Carlo Rainaldi – a favourite of Peter Eisenman because of the syntactic relations shared with Palladio; the façade of San Carlino by Borromini; a couple of Viennese buildings by Adolf Loos; and fireworks. More predictable, however, is the presence of fruit, vegetables and stones.

Generally speaking, Graziani prepares his models and still lifes as does a painter and we must turn to painting comparisons to try and solve the enigma posed by these photographs. The enigmatic mood is peculiar to more than one early-20th century Italian painting current: from the modern classicism of the Novecento group to the Appolinean air of Valori plastici (for which Roberto Longhi published his rediscovery of Piero della Francesca, always a key compositional reference of Guido Guidi) and the isolation of familiar objects, thus become alienated and alienating, of metaphysical painting – see Giorgio De Chirico’s pictures L’enigma dell’ora, L’enigma dell’oracolo, L’enigma di un pomeriggio d’autunno and more.

Indeed, Graziani is one of the founders of the San Rocco magazine, published since 2010 in English. It has embraced a “classically modern” koinè, at least in its intentions, and rediscovered axonometric projection as a preferred form of representation (the most alienating, in fact) with a vague, and certainly involuntary, affinity with the magazine 900 edited by Massimo Bontempelli (not to be confused with the “Novecento” in letters of Venice’s Margherita Sarfatti), published only in French. Although this is not the place to discuss it, the shared desire to be alienated from all phenomena of custom and fashion that distinguished San Rocco eventually itself constituted a new fashion or, at least, a certain current taste, opposed to the iconic and hedonistic excesses of the blobs and renderings of the previous two decades – yet another return to order, basically.

There are strong overtones of magic realism or real maravilloso – given his great knowledge of South American literature – also in the brief but significant written piece by Nanni Cagnone, refined poet and publisher who has worked for years with the Mazzoli gallery (“I can’t believe there are inanimate objects.”). Bizarre, to say the very least given the Dadaist finale, is the testimony of Pier Paolo Tamburelli, another San Rocco founder, almost as stirring trouble.